I recently did a four week leadership talk at our church. We spent four consecutive Wednesday nights walking through the leadership principles in Andy Crouch’s great little book Strong and Weak (which I have reviewed here). On the third week we talked about exploitation. For Crouch, exploitation happens when we seek to have power without vulnerability. Most of us, of course, don’t think that we are the type of people who seek power without vulnerability, only “those” people do things like that. But aren’t there a thousand ways we might do exactly this? As a thought experiment, Crouch asks that we imagine the eighteen-year-old version of ourselves at a party feeling rather awkward. He writes:

“What if I could hand something to the eighteen-year-old version of you walking into that party [that scared you so much] – something you could hold in your hand, something that would increase your authority and decrease your vulnerability? Something that as you held it–and sipped it–gradually eased your discomfort and enhanced your excitement? It wouldn’t be strictly legal, in the United States at least–but it would be very appealing indeed.” (p. 96)

Alcohol. He’s not talking about a glass of red with a steak dinner, of course. In this example the alcohol is being used for the dual purpose of: a) boosting your authority in the crowd and b) lowering your social vulnerability. Honestly, this doesn’t seem all that bad right? The problem here lies not so much in the drink itself but in our desire for an increase in authority and decrease in vulnerability. It’s a problem because to really flourish as a human the two must coexist. Take vulnerability out of the equation and you are not only heading towards exploiting others – which you are – but of being exploited yourself! Crouch explains:

“Over time, as with all addictions (and all idols), the effect begins to wear off. A higher and higher dose is needed for the same effect. And gradually, the thing that once delivered authority without vulnerability begins to expose you to risk and rob you of authority. In the long run, unless you are delivered by a miracle of grace, you will find that the very thing that promised authority without vulnerability has betrayed you, handing you over to the depths of suffering–vulnerability without authority.” (96–97)

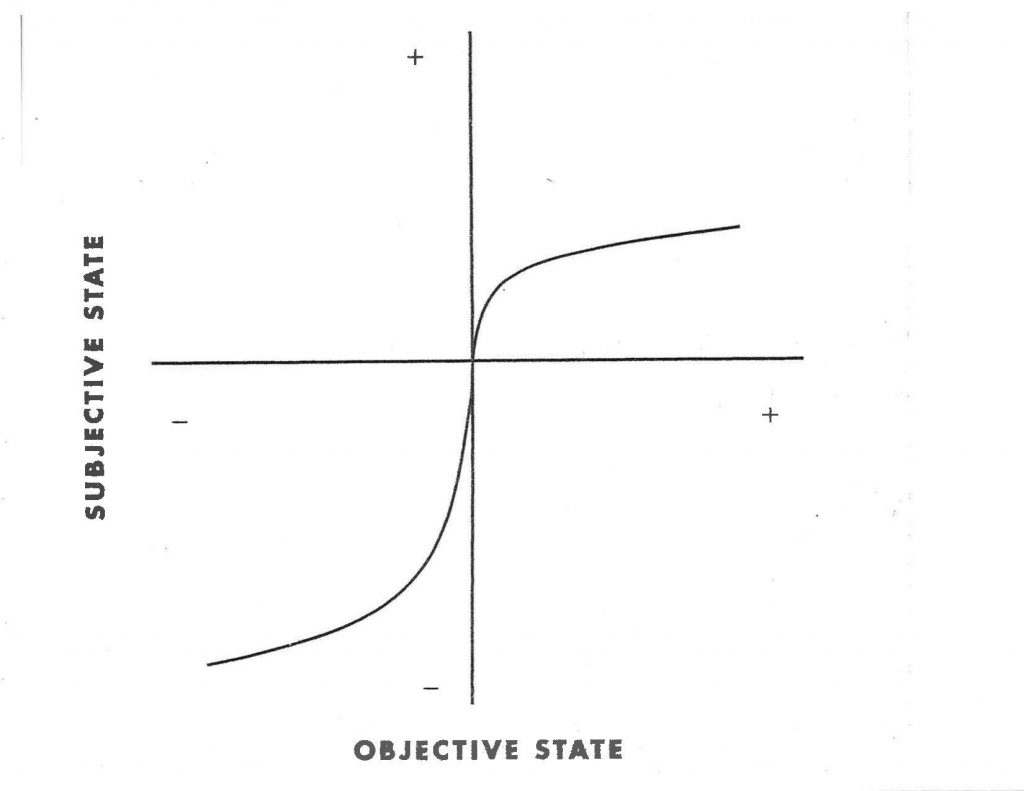

Years ago I read a fascinating book called The Paradox of Choice by Barry Schwartz. I was really intrigued by Schwartz’s exploration of the “law of diminishing returns.” To understand this law, let’s do another thought experiment. Suppose you and I got together for a meal. Sometime during the course of said meal – because I was feeling generous – I gave you $100. Sounds good, right? But wait, there’s more! After giving the $100 – because I was also feeling mischievous – I let you know that you could double that gift, but with a catch. If you decided to, you could choose heads or tails on a coin flip and, if you got it right, would double your money. The catch, though, is that if you got it wrong you would have to give me the initial $100 back and would be left with nothing. Interestingly, most people would choose to keep the $100. Not everybody of course, but the vast majority. Why? Schwartz demonstrates why using this graph:

We can learn a few things from this graph. First, we will notice that loss is actually felt more than gain. The loss of the money hurts more than the thrill of gaining the same amount of money. This is why most people have such a strong “loss aversion.” Second, the gain is felt most strongly at the beginning and then tapers off. The truth is, according to Schwartz, that you wouldn’t feel twice the pleasure from gaining $200, you would only feel 1.7 times better.1 This pattern continues and the author explains that “as the rich get richer, each additional unit of wealth satisfies them less.”2

Why does this matter? It matters because what idols have to offer is really enticing. But buyer beware because what an idol offers is always best at the beginning. They understand, and understand well, the law of diminishing returns. That, of course, is why you always need more and more of what your idol has to offer (money, alcohol, porn, food, drugs etc.). The pleasure, so great at first, lessens over time. This is how an idol robs you and gets you in its grip.

So the evening after I taught on this I was sitting at a café reading Eugene Peterson’s book As Kingfishers Catch Fire where he mentioned something that I wish I had thought of before teaching that session. Peterson draws our attention to the language of increase in Isaiah chapter 9. Look at these two sentences:

“Thou hast increased its joy; they rejoice before thee as with joy at the harvest.”

-Isaiah 9:3.

And then this:

“Of the increase of his government and of peace there will be no end.”

-Isaiah 9:7

God never offers us authority without vulnerability. Ever. That’s the game of idols. Follow God and you will most certainly know vulnerability. But unlike idols, God does not offer the best first. God is the God of increase. There’s always more. Always better. God breaks the law of diminishing returns.

Perhaps the best way to end this post is by talking about alcohol, but a little differently this time. In the gospel of John we learn that Jesus’ first miracle was turning water into wine; a troubling miracle for some (North American) conservative Christians. Here’s the interesting thing about this miracle: Jesus does it at the end of a wedding celebration. The master of the banquet, having no idea what had taken place said, “Everyone brings out the choice wine first and then the cheaper wine after the guests have had too much to drink; but you have saved the best till now.”3 He alerts us to how things normally work: bring out the best first and then, once people are too tipsy to notice, give them the cheap stuff. This is the economy of idols. But this is not the economy of God! With God there is no cheap stuff. Jesus always saves the best for last, and then – surprise! – He gives us more, and better. This is the way of God. And, if you can imagine it, of His increase…there will be no end.

Hallelujah.

1 Barry Schwartz, The Paradox Of Choice: Why More Is Less. p. 69

2 ibid. 69

3 John 2:10; Crouch writes about this in his book Playing God:Redeeming The Gift Of Power (pp. 108-111)